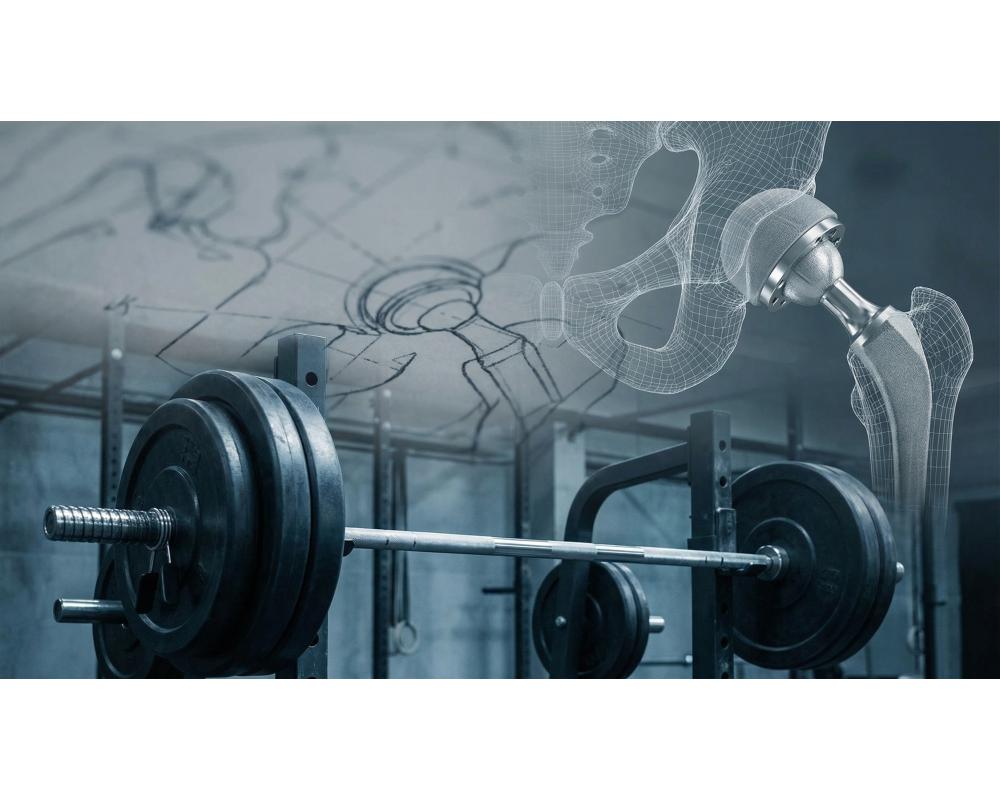

If I return to lifting heavy weights after a total hip replacement, does my implant risk ripping itself out of the socket? And how much can I lift after a total hip replacement? These are the key questions I wanted to answer as I returned to strength training post-THA (THR).

One key challenge for athletes recovering from a hip replacement is the lack of clear, accessible information on how quickly they can return to training and what volume or weight is safe to lift. For context, I'm a 36-year-old male who had a posterior-approach total hip replacement about 3.5 months ago at the time of writing, and I wanted a way to think about risk.

Executive Summary (for people who won't read the full article)

Important: This is NOT medical advice. I am not a clinician, sports, or medical professional. The maths in this article is a simplified model built from public sources and assumptions that could be wrong. Do not copy the numbers or graphs for your rehab or training. Use your surgeon and physiotherapist's guidance as your source of truth.

What this article is: one lifter's attempt to sanity-check "is heavy lifting likely to catastrophically break a hip replacement?" by combining (a) bone/implant fixation concepts, (b) published force data (kN), and (c) a conservative, assumption-heavy model.

What this article is not: a personalised "safe kg limit," a rehab plan, or a substitute for your medical team.

Who this is for: lifters and active people who already have a THA/THR and want a clearer mental model for what risks matter when (early fixation, mid-term fracture risk, long-term wear), using public sources and conservative assumptions.

Who this is not for: anyone looking for a personalised rehab plan, a “safe kg number”, or permission to override their surgeon/physio restrictions.

- Plain-English takeaways:

- Early on, the weak link is fixation to bone (osteointegration), not the metal implant "snapping". Before bone ingrowth is mature, too much motion/twisting can compromise fixation.

- Hip joint forces are measured in kN and can be surprisingly high even in normal life. Stumbling and heavy squatting can both create peak hip contact forces around the same ballpark (~10-12 kN) in the sources I cite.

- The scary failures are usually biomechanical events, not "the cup gets punched through". Think: twisting under load, falls, uncontrolled reps, impingement/edge loading, and (especially) femoral-side fracture risk early on.

- Long-term wear is mostly about cycles and bad contact conditions. "A lot of reps for years" and "edge loading / microseparation" matter more for wear than one controlled heavy single (but heavy singles can still increase risk via technique breakdown).

- If you only read one safety point: the first ~6 weeks (and often longer) are not a "how far can I push it?" phase. Follow your surgeon/physio's restrictions even if any graph looks permissive.

Quick navigation:

- Disclaimer

- Thinking About the Problem (failure modes + mechanics)

- Measured Hip Contact Forces (kN) + contact pressure

- Rate of Osteointegration

- How Much Can I Lift? (graphs + conversion back to barbell load)

- Long-Term Wear (Archard framework)

- Limitations + practical decision framework

- Updates

- Conclusion + key takeaways

- Appendix

Key Concepts (60 seconds)

- Total hip arthroplasty (THA, sometimes called THR): replacing the ball-and-socket joint with a stem/head (ball) and a cup/liner (socket).

- Osteointegration: bone growing into/onto the implant surface over months. Early on, the bond is weaker and vulnerable to micromotion.

- kN (kilonewtons): a unit of force. 1 kN = 1,000 N. Many hip-force studies report peaks in kN.

- MPa (megapascals): "pressure/stress" (force per area). 1 MPa = 1 N/mm².

- kgf-equivalent: a convenient way I sometimes express force as "kg-ish": kgf ~ N / 9.81. This is not barbell weight.

- Contact patch / edge loading: the liner doesn't carry force across the whole cup; it carries force on a smaller contact area ("contact patch"). Edge loading is when the femoral head loads near the rim/edge of the liner so the contact patch becomes smaller and more concentrated. When that happens, contact pressure spikes and wear/damage risk increases.

TL;DR (graphs/data first): If you want just the output of my model, here is the graph showing how I estimated what I can probably safely deadlift and squat after a total hip replacement based on levels of bone osteointegration. (Again: please read the disclaimer below - the model could be wrong, and copying it could be risky.)

Note: This graph estimates the maximum single-lift capacity based on implant and bone-interface strength-it models the risk of catastrophic failure, not long-term wear from repeated use. For considerations on how heavy lifting over time may affect implant longevity, see the Long Term Wear section below.

Disclaimer

I am not a clinician, sports, or medical professional, and this article is not clinical or medical advice. Please take the information in this post AS-IS.

The calculations in this post are based on numerous assumptions, some of which could be wrong. I've tried to base these on sensible, researched assumptions, which I will outline in the article. However, as with any model, if any of the assumptions are incorrect, the results could be inaccurate, potentially by a large margin. It's also important to remember that the human body varies from person to person. Some individuals may recover more quickly, while others might take longer, so what is safe for one may not be safe for another. This article is not intended as a guide, nor is it medical advice. You should always consult your surgeon and physiotherapist and not rely on the numbers in this blog. What I'm doing here is simply sharing my own decision-making process for informational purposes only. Please ensure that your surgeon and qualified physiotherapist guide your recovery process. Lifting weights that are unsafe for your stage of recovery could lead to catastrophic consequences, including implant failure, revision surgery, and serious health issues.

And 100% do not go and think, "Andrew's graph says 400KG, so it's safe for me to go and YOLO a 400KG 1RM". That is not the spirit of this article.

Thinking About the Problem

Osteointegration as the limiting factor

The force that my hip can take is not just based on the strength of the implant itself but also its durability and the process of osteointegration, which is the level and success of the implant's integration with the bone over time. Osteointegration is a gradual process, and until it's fully established, the implant's ability to bear weight will be restricted by the strength of this bond.

Beginner summary: In the early months, the limiting factor usually isn't "will the metal break?" It's "has the implant bonded strongly enough to my bone yet?" Until that bond is mature, big loads (especially twisting/jerky ones) can cause harmful micromotion.

Although this post focuses primarily on the implant and osteointegration, it's also important to remember that muscular recovery plays a big part of how quickly and how heavy I could return to training. Muscle strength and coordination are essential to your overall recovery, and while I'm not delving into that here, I work closely with my physiotherapist and coach to ensure we're clear on what is safe from a muscular perspective. Ignoring muscle recovery could lead to complications, so it's something that must not be overlooked during rehabilitation.

Deciding what forces matter in my estimations

Understanding My Implant Components

Before diving into force calculations, it's important to understand the three distinct components that make up a modern total hip replacement:

- Femoral Head (OXINIUM): This is the ball that sits on top of the femoral stem. My head is made of OXINIUM-oxidised zirconium-which is a zirconium-niobium alloy core (97.5% Zr / 2.5% Nb) that gets heat-treated so the surface transforms into a thin ceramicised layer (~5 um). You get "metal toughness" behaviour with a hard ceramic-like surface, which reduces scratching and polyethylene wear versus cobalt chrome. (ISO 14242-1:2014)

- Acetabular Shell / Cup: This is the porous titanium or titanium alloy hemisphere that gets press-fit into the pelvis. This is what bonds to bone via osteointegration-and it's the shell-bone interface that determines early fixation strength.

- Liner: This sits inside the shell and provides the bearing surface for the femoral head. Mine is highly crosslinked polyethylene (HXLPE / XLPE). The liner is where long-term wear matters most.

This distinction matters because different failure modes affect different components, and the "strength" of each is measured differently.

Three Distinct Failure Modes (Limit States)

Rather than trying to convert everything into a single "kg capacity" number, it's more accurate to think about three separate limit states:

1. Fixation / Micromotion Limit (Early Risk)

In the first weeks to months, the main concern is whether the shell-bone interface can resist shear and torsional forces before osteointegration is complete. Excessive micromotion (>150 um) can prevent bone ingrowth and lead to fibrous fixation or loosening. This is why surgeons are cautious about loading in the first 6-12 weeks.

2. Periprosthetic Fracture / Femoral-Side Issues (Early-to-Mid Risk)

Statistically, the femoral side is the weak link in the first postoperative year. Registry data shows 0.4-3.5% incidence of periprosthetic femoral fracture (PFF) after primary THA, with cementless stems and high early activity being the main risk factors. The typical cause is uncontrolled torsion-such as heavy "good-morning" fails or twisting under load-not "the cup gets punched through". (Bioscientifica)

3. Liner Contact Mechanics + Wear (Long-Term Risk)

Over years, the XLPE liner experiences wear from repeated articulation against the femoral head. This isn't about "crushing" the liner with a single heavy lift-it's about cumulative wear over millions of cycles, affected by contact pressure, sliding distance, edge loading, and microseparation events.

My earlier versions of this article tried to unify these into one "kg limit" framework, but that's not physically tidy. Each limit state has different mechanics and different timescales. Keep this in mind as you read the calculations below.

Beginner summary: There isn't one single "strength number." Early on, the worry is fixation/micromotion. Mid-term, the femur/stem side can be the weak link (fracture risk). Long-term, the worry is liner wear from years of use.

About OXINIUM (Femoral Head Material)

Since my femoral head is OXINIUM, here's what the evidence says about its wear characteristics:

Now, the bit I originally liked (and still like) is that they've run very long simulator tests: e.g., hip simulator work where OXINIUM heads against highly crosslinked PE liners ran out to ~45 million cycles with no measurable loss of oxide thickness reported in that summary.

But I need to be precise about what this means:

- Those simulator protocols are typically based on ISO 14242-style loading, which uses a dynamic axial load of ~0.3-3.0 kN (roughly 30-300 kgf) with prescribed motions. That's not "equivalent to deadlifting X kg", because barbell load doesn't map 1:1 to hip joint reaction force (muscle forces dominate the internal joint compression), and the simulator is about tribology (wear), not "max strength until something snaps". (Springer)

- Even Smith+Nephew's own evidence pack basically says (paraphrasing) "simulator wear isn't proven to quantitatively predict clinical wear", so treat it as directional reassurance about wear resistance, not a certification of safe powerlifting limits.

So: the simulator evidence is strong for "this bearing couple is unlikely to explode from wear when treated reasonably", but it's not a licence to convert cycles + kN into "therefore 300 kg deadlift is fine".

This tells us about the ability to handle wear with a reasonable force through many repetitions over time, but it does not tell us much about the more extreme forces that the implant can handle.

Compressive and shear forces play a role when performing movements involving the hip joint, and both of these forces affect the implant's performance and durability. So before I can model the scale of the weights I can lift at each stage of recovery, I first need to calculate the fully-osteointegrated bone-implant interface strength when put under shear and compressive forces.

Shear Strength

Shear force occurs when two surfaces slide past each other, creating stress along the interface.

It was initially challenging to find specific levels of shear and compressive force that the joint could withstand, but I found two relevant studies on hydroxyapatite-coated implants, which is relevant as Oxinium implants are commonly paired with this coating. In a study by Hayashi et al. (1993) and another by Castellani et al. (2010), they demonstrated that these implants could withstand shear forces ranging from 4 to 12 MPa. Both have different materials and mechanisms, but this provides a useful benchmark for understanding the kinds of forces an osteointegrated implant may endure.

A megapascal (MPa) measures pressure or stress, indicating how much force an implant can handle per unit area. For implants, MPa values help quantify their resistance to forces like shear or compression. While MPa measures force per area, implant size matters too-larger implants spread forces over more surface area, reducing stress, whereas smaller implants concentrate it, affecting overall durability.

Therefore 4-12 MPa doesn't yet make much sense to us on its own, and to calculate what this means in terms of force, we need to convert it to newtons based on the surface area of the implant. Given most acetabular shells (porous titanium cups) have a surface area of 5,000-10,000 mm², let's go with the lower end of 5,000 mm².

Beginner summary (units): MPa is "how much force per square millimetre." To get a total force estimate, you multiply MPa by an area. This step is one of the shakiest parts of the model because real load isn't evenly spread over the whole cup surface (I call this out in the caveat below).

Let's now convert this 4-12 MPa to force accounting for the 5,000 mm² surface area of the outer shell at the bone-implant interface. Note: when I express forces as "kg", I mean kgf-equivalent (kilograms-force), i.e. N / 9.81-not kilograms of mass.

- Lower Range:

Force = 4MPa x 5000mm² = 20,000 N

20,000 N = 2,038 kg - Upper Range:

Force = 12MPa x 5000mm² = 60,000 N

60,000 N = 6,118 kg

For the sake of our estimates, I will be risk-averse and go with the lower number calculated based on 4 MPa. Picking the lower range means when my implant is fully osteointegrated, my bone-implant interface can likely take the lower end of this range: 2,038 kgf-equivalent of shear force (~20,000 N).

Important Caveat: Why 'MPa x total cup area' overstates implant-bone capacity

When an FEA paper says "peak von Mises stress in cancellous bone = 70 MPa" (or similar), that is a local peak, typically at the superior dome / rim region where load concentrates. It is not telling you that the entire cup-bone interface is sitting at 70 MPa.

So if I multiply 70 MPa by the full 5,000 mm² and get "350,000 N", I've implicitly assumed the whole interface is simultaneously experiencing the peak stress, which is physically the same mistake as assuming every square millimetre of a car tyre tread is at the peak contact stress at once. It isn't.

A more honest first-principles approach is:

- Use joint contact force (kN) as your "global" load.

- Use FEA stress results as evidence about where the load concentrates and which failure mode dominates (often micromotion / shear early, fatigue/loosening long-term, edge loading for liners, etc.).

- If you still want a force-style "capacity" number, introduce an effective load-bearing area fraction, because most of the load routes through the superior region.

If you assume (for example) only 20-40% of the porous surface is doing the serious work at peak load (superior dome contact, plus whatever is well-integrated), then your interface shear capacity drops by ~2.5-5x compared with using the whole 5,000 mm². That one change makes the numbers much more realistic. Keep this caveat in mind when interpreting all the force calculations below.

Compressive Strength

Compressive Strength is the maximum pressure an implant can handle before structural failure, particularly relevant to load-bearing joints like hip implants.

A study by Kurniawan et al. (2011), using finite element analysis, examined the bone-implant interface under varying degrees of osteointegration. The analysis showed that, at full osteointegration (100%), the bone-implant interface can handle up to 70 MPa of stress at critical regions. This value provides a realistic estimate for the compressive strength of an acetabular cup implant.

UPDATE

Recent push-out experiments on modern porous-titanium cups report failure stresses of around 40-60 MPa, depending on porosity and bone quality (MDPI). As these laboratory values sit approximately 30% below the 70 MPa FEA peak I quoted earlier, I'll use 50 MPa as a more conservative real-world ceiling for the rest of this post. All subsequent compression values (and graphs) still apply the 1/2 safety factor, so nothing else in the model changes-only the implicit margin of safety increases.

To convert this to force, using the assumption of a 5,000 mm² acetabular cup interface, we can calculate:

- Force = 50 MPa x 5000 mm² = 250,000 N

250,000 N ~ 25,484 kgf of compressive load capacity.

This gives us a clearer picture of the significant compressive forces these implants can withstand, reinforcing the reliability of Oxinium implants even under high-stress conditions. The combination of strong material properties and surface coatings like hydroxyapatite helps maintain implant stability and integrity

For tolerance, let's halve this and choose ~12,742 kgf as our bone-interface maximum allowable compressive force limit.

Beginner summary: Compression is "pushing straight into the socket." The calculated compression numbers end up very large, which is why I don't think "the cup gets punched through" is the realistic failure story for controlled lifting. The early risks are more about motion/twist and fixation quality.

Which is the weak link: the bone-implant interface, or the materials?

While the implant materials-the OXINIUM femoral head, titanium shell, and XLPE liner-are engineered to withstand incredibly high forces, well beyond the stresses encountered during daily activities, it's important to remember that the bone-implant interface is much weaker. The OXINIUM head material itself has compressive strengths exceeding 2,000 MPa.

Compressive Strength of Plastic Lining (Contact-Patch Approach)

UHMWPE / XLPE liner "strength" is best thought of in terms of yield stress and creep/relaxation, not ultimate compressive failure. One useful ballpark is yield stress on the order of ~18-24 MPa (varies by formulation and irradiation, but that's the right scale). (Sangir Plastics)

Critically, the liner doesn't see load over the whole hemispherical surface; it sees it over a contact patch that can be hundreds of mm², not thousands (and it shifts during motion). That's why liner design papers talk in contact pressure / contact stress (MPa), not "total force over the full cup area".

Now the key trick:

1 MPa = 1 N/mm², so if your instantaneous contact patch were, say, 300 mm², then "20 MPa worth of yield" corresponds to about:

- Force at yield ~ 20 N/mm² x 300 mm² = 6,000 N

- In kgf: 6,000 / 9.81 ~ 612 kgf

If your patch is 500 mm², that becomes:

- 20 x 500 = 10,000 N ~ 1,019 kgf

So the liner can tolerate big loads provided the contact patch is not tiny (and in reality it grows under load because the polymer deforms a bit, which is exactly the point).

Also, XLPE is viscoelastic, meaning the peak stress is not "frozen"; it relaxes as the contact area increases. There's published data showing that under a constant load the contact area increased and peak stress dropped over short time scales (seconds -> minutes), i.e. the material "settles" rather than staying at the initial peak stress forever.

Implication (the bit you care about): a single heavy rep is not automatically a "liner killer" just because it creates a high instantaneous force; wear and damage depend heavily on sliding distance, edge loading, microseparation, and cycles.

OXINIUM femoral head force capacity:

- Force = 2,000 MPa x 3,000 mm² = 6,000,000 N

6,000,000 N ~ 612,244 kgf-equivalent - (This is so far beyond any realistic joint load that the head is never the limiting factor-it's included here only to show that the metal is not the concern.)

10-XLPE (Poly Liner) force Capacity (using 500 mm² contact patch as a reasonable estimate):

- Force at yield ~ 20 MPa x 500 mm² = 10,000 N

10,000 N ~ 1,019 kgf

Given the above load calculations using a contact-patch approach, a simple "yield stress x contact patch" estimate implies approximately ~1,019 kgf at yield (based on ~20 MPa and a 500 mm² patch). This is a more realistic way to think about liner loading than multiplying stress by the full cup surface area.

Next, let's define the actual model inputs I use for the graphs. To keep this approachable, I treat these as conservative, order-of-magnitude ceilings rather than exact limits:

- Interface shear capacity (per hip, fully integrated): ~1,019 kgf (this is the conservative 4 MPa x 5,000 mm² estimate converted to kgf-equivalent, then halved as a safety factor). If you assume the load is shared evenly across both hips in a bilateral lift, that's ~2,038 kgf combined.

- Liner / contact-force scale (per hip): ~1,530 kgf (~15 kN). This is not a "liner failure force"; it's a practical peak hip contact-force scale (kN neighbourhood) used to keep the model anchored to in-vivo telemetry/modelling. Liner risk is better discussed in terms of contact pressure (MPa) via contact-patch area; for reference, a simple yield-stress x patch-area estimate gives ~1,020 kgf at ~20 MPa and 500 mm².

- Load-sharing simplification: I assume (a) about half bodyweight acts "above the hip" as external load and (b) a bilateral lift shares external load roughly 50/50 across hips. This is a modelling convenience, not a biomechanical law.

Note: These numbers are more conservative than my original calculations because they account for realistic contact patch areas rather than the full liner surface. Remember that a single heavy rep is not automatically a "liner killer"-wear depends heavily on sliding distance, edge loading, and cycle count rather than peak instantaneous force alone.

Model Inputs (Summary in One Place)

If you only want to sanity-check what the graphs are built from, here are the key model inputs and simplifications in one place:

| Input | Value used | Why it matters |

|---|---|---|

| Interface shear capacity (per hip, fully integrated) | ~1,019 kgf-equivalent (after safety factor) | Early months are typically fixation/micromotion-limited; this is the main early ceiling in the model. |

| Liner/contact-force scale (per hip) | ~15 kN (~1,530 kgf-equivalent) | Anchors the model to measured hip contact forces; later-month curves plateau when this dominates. |

| XLPE yield stress (ballpark) | ~18-24 MPa | Material scale for contact-pressure discussion (not a single “failure force”). |

| Contact patch (illustrative) | ~500 mm² (centred), ~300 mm² (edge-loading scenario) | Converts kN-scale forces into MPa-scale contact pressure; edge loading makes pressure spike. |

| Load-sharing simplification | (barbell + 0.5 × bodyweight) / 2 (per hip) | Simple mapping from external load to per-hip external load for bilateral lifts. |

| Osteointegration progression | Logistic curve, “~9 months to full” (rough) | Scales fixation-related capacity down in early months. |

| Exercise multipliers | Chosen to land in the ~10-15 kN neighbourhood for heavy efforts | Connects external load to internal per-hip force; technique/depth changes can shift these. |

Anchoring on Measured Hip Contact Forces (kN)

Rather than relying on spine-based force multipliers and trying to convert them to hip loads, a more defensible approach is to anchor on actual measured or modelled hip joint contact forces. Two solid data sources exist:

Beginner summary: Instead of guessing "barbell weight -> hip force" from scratch, I anchor the model to published measurements (in kN) of what hips actually experience during events like stumbling and heavy squatting.

Real-World kN Anchors

1. Instrumented Hip Implants (OrthoLoad / Bergmann)

Telemetry from instrumented hip implants shows that "stumbling" peaks produce hip contact forces around ~11,000 N (11 kN). This represents the kind of sudden, uncontrolled loading event that implants must survive. (OrthoLoad)

2. Elite Powerlifter Squat Modelling (PLOS ONE 2025)

A biomechanical analysis of elite powerlifters found peak resultant hip contact forces during heavy squats (at 90% 1RM) of approximately 15.5 +/- 3.0 x bodyweight. For a 78 kg lifter:

• BW force = 78 x 9.81 ~ 765 N

• Peak hip contact force = 15.5 x 765 ~ 11,858 N (~12 kN)

(PLOS ONE)

Key insight: Maximal squatting in elite lifters produces hip contact forces in the same kN neighbourhood as stumbling events. This is why those "big scary" in-vivo numbers keep showing up-they're not fantasy; they're what the hip joint actually experiences during high-demand activities.

For deadlifts, the exact mapping is less well-studied, but given similar hip extension demands and muscle force paths, it's reasonable to assume deadlifts produce forces in the same order of magnitude-likely 10-15 kN for heavy pulls.

Why I No Longer Use Spine-Based Multipliers for the Hip

My earlier version cited Cholewicki et al. (1991) on lumbar spine loads and tried to apply those multipliers to the hip. That approach is problematic because hip joint reaction force is dominated by muscle force paths that don't scale like spine shear multipliers. The hip sees huge compressive loads from the gluteals, hip flexors, and adductors that aren't captured by "barbell weight x 4".

Using measured hip contact forces (kN) as the starting point is more defensible than converting spine data.

Converting kN to Liner Contact Pressure (MPa)

The liner doesn't see load over its whole surface-it sees it over a contact patch that varies with head size, liner geometry, and loading angle. This is where "materials" actually matters:

- Pressure (p) = Force / Area

- With 12 kN peak force:

| Contact Patch | Contact Pressure | Implication |

|---|---|---|

| 500 mm² | 12,000 / 500 = 24 MPa | Near the upper end of typical XLPE yield (~20-24 MPa); centred loading and patch growth matter |

| 300 mm² (edge loading) | 12,000 / 300 = 40 MPa | Above yield-risk of plastic deformation if sustained |

This is the real materials question: are you creating edge-loading or tiny-patch scenarios that drive contact pressures into the nasty zone? A centred, well-articulating head distributes load across a growing contact patch (the polymer deforms to spread the load). Edge loading or microseparation events concentrate load on a small area and create problems.

Squat Force Multipliers (for Reference)

Regarding the hip and spine during squats, studies indicate that squat depth significantly affects internal joint forces. Hartmann et al. (2013) found that deep squats can produce compressive forces up to 10 times body weight on the lumbar spine and between 6 to 10 times body weight on the hip joint due to increased hip flexion and muscle activation. Shear forces on the lumbar spine during deep squats range from 1.3 to 3.5 times body weight because of greater forward trunk lean, while shear forces on the hip joint are estimated between 1.0 to 2.0 times body weight.

UPDATE:

Hip-implant telemetry shows that controlled, full-depth squats (less than 95° knee bend) generate peak resultant forces of 2.8-3.5 x body weight (BW) in most THA patients, with the highest subject in the Bergmann cohort peaking at 4.2 x BW (PMC). These in-vivo values are lower than the 6-10 x BW multipliers derived from spine modelling, mainly because hip flexion torque is distributed across both legs and trunk angles are smaller than in a "good-morning" style deep squat. I've therefore kept my compressive multiplier range at 6-10 x BW to stay on the safe side, but readers should note that everyday squats-with disciplined tempo and controlled torso position-likely fall at the lower end of that range.

As a powerlifter, I took pause at that. Deep squats have a larger force multiplier mainly due to higher forward trunk lean. Therefore, I'd expect that a low bar squat would similarly result in higher leverages compared to a high bar squat. So, in my training, I intend to consider a low bar squat akin to a deep squat, even if I limit the range of motion to hitting parallel.

What is also very interesting to learn is that, in contrast, shallow (partial) squats reduce these forces significantly. Compressive forces on the lumbar spine and hip joint decrease to approximately 4 to 6 times body weight, and shear forces on the lumbar spine lower to around 1.0 to 2.0 times body weight. Shear forces on the hip joint during shallow squats are minimal, often less than 1.0 times body weight.

Therefore, to ensure a conservative and safe approach, I will select a compressive force multiplier of 6 to 10 and a shear force multiplier of 2.0 to 3.5 for deep squats. For shallow squats, the compressive force multiplier can be adjusted to 4 to 6, and the shear force multiplier to 1.0 to 2.0. These multipliers account for individual variability and the increased forces associated with deeper squat depths.

Again, it makes sense why my surgeon advised me to avoid squatting below parallel in the early weeks of recovery given how much higher the shear and compression ratios are relative to a more shallow squat.

The Hartmann et al. (2013) study defines shallow squats as those with a knee flexion angle of 0° to 50°, and deep squats as those with 90° or greater knee flexion, affecting joint loading and muscle engagement.

Summary: kN Anchors vs Force Multipliers

For squats, I've retained the literature-based multipliers (with the caveats noted above). For deadlifts, I now prefer anchoring on measured hip contact forces directly:

- Deep Squat: Peak hip contact force ~15.5 x BW (from PLOS elite powerlifter data), or ~12 kN for a 78 kg lifter

- Shallow Squat: Significantly lower forces due to reduced hip flexion and trunk lean

- Deadlift: Expected to be in the same order of magnitude as squats (~10-15 kN for heavy pulls), though less directly studied. The OrthoLoad "stumble" data (~11 kN) provides a useful upper bound for sudden loading events.

The key insight is that maximal lifting in elite athletes produces hip contact forces comparable to stumbling events-forces that modern implants are designed to survive. The question isn't "will the metal fail?" but rather "am I creating bad tribology conditions (edge loading, microseparation) that accelerate wear?"

For clarity, in the updated (kN-anchored) model I treat "multipliers" as a simple mapping from external load to internal per-hip force:

- External load (per hip) ~ (barbell + 0.5 x bodyweight) / 2

- Internal force (per hip) ~ multiplier x external load (per hip)

I then choose the contact-force multipliers so that a heavy lift lands in the same kN neighbourhood as the measured data (e.g., ~11-12 kN peaks), and I keep the interface-shear multipliers separate (because liner contact stress and interface micromotion are different mechanics).

Rate of Osteointegration

The next critical piece of information we need to consider is the speed of osteointegration in the hip joint: Clearly, if the process of the implant fixing itself to the bone is only 25% complete, then it is not going to be able to take the full force it otherwise might be able to when the osteointegration process is complete. Given that I intend to return to powerlifting much sooner than the date of full osteointegration, I need to be able to model what I should be lifting at any given point post-surgery.

Beginner summary: This section is basically: "how fast does the bone-implant bond mature?" I use a simple S-shaped curve as a rough guess so I can scale the early-month limits downward.

Osteointegration is unlikely to happen linearly. Biological processes often follow a logistic curve, meaning progress is initially slow, accelerates exponentially, and then reaches a phase of linear progression before tapering off towards the end. This pattern allows us to model the recovery period and estimate how quickly integration happens.

This pattern mirrors real-life dynamics, such as how cells divide, how tissues repair, or how populations grow, where growth initially lags, then accelerates when resources are abundant, and finally plateaus as limitations like nutrients, space, or biological feedback set in. Its ability to capture this S-shaped trajectory makes it ideal for modelling processes that involve constrained growth or saturation, providing a realistic and predictable framework.

Based on case studies, full osteointegration with the implant typically occurs by month nine. Armed with this knowledge and using the logistic curve, we can estimate the percentage of osteointegration at different points in time, which will help determine the percentage of force that can be applied through the joint. That looks a little like this:

This logistic-curve graph models my estimates for the level of osteointegration each month: around 10% in month two, 25% by month three, 50% in month four, and so on. This information is useful as I can apply these percentages to the theoretical maximum weight I can lift at full osteointegration to get an estimate of what the maximum I should be lifting is at each stage of recovery.

For example, I expect the maximum amount I can lift when the implant is only 50% osteointegrated is likely to be half of what I can lift when fully osteointegrated.

How Much Can I Lift? Crunching the Numbers

Now that we have all the force estimates for liner/contact stress, interface shear, and osteointegration percentages at each given month, we can calculate the maximum force on one hip at each stage and then convert that back into a barbell load for a bilateral lift.

Beginner summary (what the graphs mean): I'm not claiming "X kg is safe." I'm showing how a set of assumptions produces a rough curve: very conservative early limits (because fixation is immature), then a plateau later (because other factors become the limiter). Treat the shape as more meaningful than any single number.

As a reminder, using the contact-patch approach: with a 500 mm² effective contact area and XLPE yield stress of ~20 MPa, the liner sees approximately ~1,020 kgf before yield. This is a more realistic figure than my earlier "total area" calculations, which overstated capacity by treating the entire liner surface as load-bearing.

When lifting with two legs, the external load is shared between them, which means the external load per hip is roughly halved. In the graphs, I model capacities on a per-hip basis (because in-vivo telemetry forces are reported per hip), and I then convert back into a bilateral barbell load using the "half bodyweight / half per hip" simplification described above.

The table below shows the per-hip force ceilings by month. Because the liner/contact-stress ceiling does not scale with osteointegration (it's a material/contact-mechanics issue), while interface shear does (it's fixation quality), the early months are shear-limited and later months plateau once the liner/contact-stress ceiling dominates.

As I'll reiterate later, my surgeon's advice was not to lift anything remotely heavy in the first six weeks. So the weight limits should be ignored in favour of caution in these early weeks.

Initially, the forces tolerated by the hip are relatively low but increase significantly as osteointegration progresses, following a logistic curve. The key point is that this table is showing internal per-hip force ceilings (kgf-equivalent), not "how much can I deadlift?".

To convert those internal force ceilings into an external barbell weight, the model uses a simple per-hip relationship:

- External load per hip ~ (barbell + 0.5 x bodyweight) / 2

- Internal demand per hip ~ multiplier x external load per hip

Then we just solve the inequality "internal demand <= ceiling" for the barbell weight. That produces the allowable-weight curves below.

To convert the maximum hip forces to weight lifted, I take the osteointegration-adjusted force values from the above table and apply:

- a contact-force multiplier (kN-anchored) for liner/contact-stress constraints, and

- a separate interface-shear multiplier for fixation / micromotion constraints.

These values also account for the external load from bodyweight using the "half bodyweight above the hip" simplification.

For example (illustrative, not advice): at month three the model estimates ~23% osteointegration. Applying that to the per-hip interface shear capacity (~1,019 kgf) gives roughly ~235 kgf per hip of interface shear capacity at that stage.

- In the refactored graph model, that maps to a deadlift "Mid (conservative)" barbell load of about ~64 kg at month three.

Note: These calculations are illustrative. The key insight is that early osteointegration is the limiting factor, not material strength.

I've subtracted half my body weight rather than all of it because I figure approximately half my weight will be above the hip joint acting as load on that joint.

Based on the above calculation, we can see at month three that I should probably avoid deadlifting above 76kg based on the maximum permissible shear force (based on the averaged midpoint) or 64kg if I want to be risk-averse. There are some additional tolerances baked into this number for safety, so a little deviance probably won't hurt at month three, but you can see how this approach can guide my training.

Now, let's calculate this for all time periods and all compression and shear ranges, selecting the lower compression or shear to act as the allowable lift limit.

For Shallow Squat:

For Deep Squat:

In the updated model, interface shear (fixation / micromotion risk) is the primary limiting factor during early osteointegration (months 1-4). Once osteointegration progresses beyond ~75%, the liner/contact-stress ceiling (~15 kN per hip) becomes the limiter, which is why the curves plateau around month 5.

One subtle but important point: deadlifts can look more restricted early because the deadlift's interface-shear multiplier is higher, but deep squats can plateau lower later because the contact-force mapping (anchored to kN telemetry/modelling) implies higher hip contact force per kg for deep squats than for deadlifts in this simplified model.

For Deadlift:

Remember that although the table includes projections for upper, average, and lower weights, reflecting the minimum, average, and maximum ranges for the force multipliers discussed earlier; If I am fully risk-averse, I should make decisions based on the 'lower' value. But it's useful to know the full range regardless.

By incorporating these force multiplier ranges, we can calculate a range of maximum allowable lifting weights for each period, ensuring the weight load remains within the allowable compressive and shear limits for both body weight and external load. This will give us a clearer understanding of what the maximum limits should be for my lifting at different stages of recovery.

As discussed, we will pay attention to the last allowable lift range, which is the lower of the shear/compression limit for each respective month and lift, when guiding my training.

Let's now map these limits onto a graph so you can appreciate them visually:

For Shallow Squat:

For Deep Squat:

These calculations and graphs are very rough estimates based on assumptions and variables that might be incorrect or ill-informed.

For Deadlift:

These calculations and graphs are very rough estimates based on assumptions and variables that might be incorrect or ill-informed.

As I review these graphs, I can see why my surgeon was so cautious during the first six weeks of recovery; They were very clear that I should avoid weighted exercises beyond light accessory work on squats and deadlifts until that point. When I asked about more taxing movements, like squatting with a low-bar position, they advised waiting until three months. The graphs clearly show why.

For context, my maximum squat is 222 kilograms and my deadlift is 245 kilograms, and I'd often lift 50-70% of this in the gym when training. So you can see why, during the early stages of recovery (between one and three months), typical gym lifts would be close to or even exceed the tolerance limits of the hip joint and implant based on the osteointegration level at that time. Pushing those limits too soon could risk compromising the implant or delaying recovery.

However, things take off beyond month three or four, and the osteointegration has progressed to a point where the weights I typically lift are unlikely to affect the implant negatively despite full osteointegration not being complete until around month nine. By then, the joint can tolerate much more, making it safer to increase the load gradually without significant concern for the implant's integration.

UPDATE: Periprosthetic Fracture & Stem Issues

While this article focuses on the cup-bone interface, the femoral side is statistically the weak link in the first postoperative year. Large registry studies report a 0.4-3.5% incidence of periprosthetic femoral fracture (PFF) after primary THA, with cementless stems and high early activity being the main risk factors (Bioscientifica). The typical cause is early, uncontrolled torsion-such as heavy "good-morning" fails or twisting under load. For that reason, my personal rule is simple: no grinding reps or ballistic eccentrics until at least month 12, even if the cup numbers suggest plenty of capacity.

What Would Actually Break First? (Failure Mode Priority)

Timeframe Primary Risk Mechanism Early (0-6 months) Torsion / Micromotion Excessive movement at shell-bone interface before osteointegration is complete -> fibrous fixation or early loosening Early-to-Mid (3-18 months) Periprosthetic Fracture (Femoral Side) Uncontrolled torsion, falls, or shock loading -> fracture of femur around stem, especially with cementless stems Long-term (years) Liner Wear / Osteolysis Accumulated wear debris from millions of cycles -> bone resorption around implant -> loosening -> revision Note that "cup gets punched through" or "head snaps" are not realistic failure modes for controlled heavy lifting. The materials are absurdly strong relative to any plausible joint load. The real risks are biomechanical events (torsion, falls, impingement) and long-term wear accumulation.

Considering Long-Term Wear (Archard Framework)

Of course, the risk of catastrophic failure isn't the only factor to consider. In addition to how much load the joint can handle, the long-term health of my joint-and whether I may need revision surgery in the future-depends on wear. So, I also need to think about what repeatedly lifting heavy weights might mean for wear on the implant, and how that could affect its longevity.

Beginner summary: Long-term wear is more like tyre wear than "one big explosion." It's driven by how many cycles you do, how far the joint slides each cycle, and whether contact conditions are good (centred) or bad (edge loaded).

Wear mechanics: the Archard equation (one-paragraph version)

The classic model for tribological wear is the Archard equation, which says (roughly) wear is proportional to load × sliding distance × cycles (with a wear coefficient that changes with contact conditions). This is why cycle count + sliding distance usually dominate the lifestyle risk story, and why the nastiest wear modes often involve edge loading / microseparation rather than smooth centred articulation.

Using the Archard framework: wear proportional to load x sliding distance x cycles. This tells us that:

- Cycle count is the dominant factor for lifestyle wear risk

- Sliding distance per cycle matters-running has significant articulation per stride; a controlled squat has minimal hip sliding

- Load increases wear per cycle, but the effect is less dramatic than cycle count differences between lifting and endurance sports

Similar XLPE materials have undergone stress testing at 10 MPa for 1.5 million cycles in lab tests, demonstrating that this material can handle high load forces for prolonged periods without failure or excessive wear. This is in addition to the research I mention in my recovery diary, showing OXINIUM heads tested against XLPE liners with a force of 4,000 N (~400 kgf in the joint) for 45 million cycles with very minimal wear.

We also need to consider that the more we use the joint under heavy load-such as deadlifting every week-the increased wear on the XLPE liner is inevitable. This wear would be greater than if the joint were not subjected to such stress. Ultimately, this comes down to a personal decision about how much risk I'm willing to take in terms of the wear I'm exposing the joint to over time. I also need to weigh up the enjoyment and personal well-being I get from these activities.

However, using the Archard framework, heavy lifting may actually be a friendlier wear profile than running:

- Two heavy lower-body sessions per week result in fewer than 10,000 load cycles per year

- Running can accumulate millions of cycles over a lifetime

- The sliding distance per rep in a controlled squat/deadlift is much smaller than per running stride

The key caveat: heavy lifting with poor mechanics, impingement, or edge loading can create nasty wear modes that don't follow the simple Archard model. The practical takeaway is that low-rep, high-control lifting with good hip mechanics is generally a friendlier wear profile than high-cycle activities.

In the coming years, I'll need to monitor for signs of wear-related issues (osteolysis, loosening). Excessive wear on the liner could result in the need for a revision surgery sooner than expected. However, given the Archard framework suggests low-rep heavy lifting is relatively wear-friendly, and the simulator data on OXINIUM + XLPE shows excellent long-term wear performance, I'm cautiously optimistic about longevity.

Limitations: A Word of Caution

Purpose of these calculations

All the numbers I've compiled in this article were to answer a personal question: whether progressing to heavier weights posed a risk of dislodging the implant in my hip socket.

I wanted to assess the risk of catastrophic failure from lifting heavy, and identify when it would be safe to start increasing the load. However, it's important to stress that I didn't adjust my training based solely on these calculations. I also followed the advice of my surgeon and physiotherapist, and there was no chance I would ignore their recommendations just because I'd run some numbers. This analysis simply helped me visualise and understand my recovery better, enabling me to make more informed decisions.

How I Actually Decide What to Lift (Practical Framework)

Important: This section is not medical advice. It's simply my personal decision framework for managing risk while pursuing strength goals after THA. Your surgeon and physiotherapist should guide your own training progression.

By the time you're well past the early healing phase (e.g., many months post-op), the question often shifts from "will the implant rip out?" to "how do I push strength without exposing myself to avoidable high-consequence events?" Here are the rules I use:

- I prioritise controlled reps over maximal reps: most of my work stays around RPE 6-8. I keep true grinders rare because technique deviations (twist, shift, ugly save) are where risk spikes.

- I progress slowly and consistently: when things feel good, I'll add small load increments (typically 2.5-5 kg) or reps week-to-week rather than chasing frequent 1RM attempts.

- I avoid "bad multipliers": no twisting under load, no rushed walkouts, no ballistic eccentrics, and I'm extra cautious when fatigued (fatigue is when form variability increases).

- I treat the 24-48 hour response as a governor: if I get persistent deep joint ache, sharp pain, instability feelings, or a limp afterwards, I would back off and reassess rather than "pushing through" (not that this has happened yet).

- I plan misses/bails: I bias toward setups and variations where I can safely bail (and I don't load weights I'm likely to fail in uncontrolled positions).

- I use the model as context, not a prescription: the graphs help me understand why early loading should be conservative and what mechanisms matter (torsion/edge loading/wear), but they don't "clear" a specific kg number.

I also reflect on the surgeon's advice not to lift anything heavy during the first six weeks of recovery. After the six-week mark, I was able to gradually resume lifting, and by the three-month point, the surgeon was far more encouraging about increasing the weight. Although we've modelled graphs predicting the potential load on the hip joint early on, I'm now beyond that period. It was still correct for me to avoid weighted exercises (or keep them to an absolute minimum) at that time.

Be risk-averse in the first six weeks (and don't add weight)

Another concern during those initial six weeks is the risk of micro-movements in the joint. These can result from lifting, but also from everyday movements, especially anything involving torsion or twisting forces. These micro-movements can disrupt the osteointegration of the joint, which could have long-term consequences for its strength and stability.

It was definitely the right decision not to overdo it early on, and others should also be cautious, particularly in those critical first six weeks: you should not have a "how far can I push the weight?" mindset in these early weeks.

Individual Factors

Individual factors-cup size, stem design, bone mineral density, pelvic tilt, even squat-stance width-can shift joint-force vectors by 10-25%. That's why the load ceilings outlined here are population-level estimate, not personal prescriptions. Get a standing AP pelvis at one and two years post-op; if there's no migration and bone density is good, I felt it was reasonable to aim for the upper 10% of the ranges provided.

There Are Other Risks

Please also bear in mind that the forces I've calculated here are based on a single lifting event, not many compounded over time. And though Wolff's law suggests that bone strength and recovery come from mechanical stress, repeatedly lifting near a theoretical maximum (if such a maximum even exists) could increase risk versus staying comfortably submaximal.

In addition, this article also doesn't cover other risks of lifting heavy, such as the impact of proper form on lift safety, muscle recovery around the incision, or risk of dislocation based on the nature, approach and risk of the movement you are doing. So, though understanding the load tolerance of the joint is useful, it's not the only factor to consider when deciding how to return to lifting safely. It's important to listen to your body and seek professional guidance.

Then, you also have the complex and hard-to-model risks of periprosthetic fracture (PFF), which I do not evaluate in this article. According to Nikolaos et al (2021)., Age, female gender, osteoporosis, and implant type (cementless implants have higher fracture risks) are notable factors increasing the likelihood of PPFs. The risk of getting one is also higher the closer you are when you have the surgery, and it reduces as osteointegration progresses. So though we can see the compressive forces of bone can be very high, there are many confounding factors which make this data point on its own unreliable.

Model Limitations (What Could Be Wrong in the Maths)

To be maximally transparent: the graphs in this article come from a simplified, non-validated model. It is not a clinical decision tool, and it is very likely wrong in some details. The biggest model weaknesses are:

- Interface shear "capacity" is a proxy: I use MPa values from specific studies and convert them to a force using a nominal cup surface area. Real initial fixation depends on press-fit, cup design, screws, bone quality, and micromotion thresholds. This calculation is best interpreted as a rough scale, not a measured limit for any individual.

- Engaged area is unknown: Load is not shared uniformly across the whole porous surface. I discuss the "effective engaged area" concept earlier, but the model still cannot know whether peak load is carried by 20%, 40%, or 80% of the interface in a given person at a given time.

- Osteointegration scaling is assumed: I model osteointegration as a logistic curve and assume fixation-related capacity scales proportionally with "% integrated". That's a modelling convenience; biology and fixation are not guaranteed to scale linearly with this percentage.

- Exercise multipliers are heuristic: The mapping from external load (barbell + partial bodyweight) to internal per-hip forces uses simple multipliers. These are not validated across different techniques (low bar vs high bar, stance width, depth, trunk angle), fatigue states, tempo, or asymmetry.

- Contact patch / edge loading is the real liner risk: Liner risk is governed by contact pressure (force ÷ contact area), and the contact patch area varies with component geometry and loading. The model does not explicitly solve contact mechanics; it uses a reasonable contact-force scale anchored to kN telemetry/modelling.

- Single-event framing: Much of the "limit" discussion is framed around peak loads. Long-term outcomes depend on cumulative exposure, technique consistency, and bad events (twists, falls, impingement), not just "how heavy was one rep".

- Not validated or calibrated to you: Even though I use my bodyweight and lift numbers, the model is not calibrated using imaging, component positioning, bone density, or instrumented measurements. Two people with "the same barbell weight" can experience meaningfully different internal loads.

Bottom line: This article represents the best model I could build from the public data I could find, with conservative choices and explicit caveats. It can help reason about shape (early fixation risk vs later plateau) and what matters (torsion/edge loading), but it should not be used as a personalised prescription for anyone's rehab or training plan.

Updates

December 2024 (6 months post-op):

Putting trust in my calculations and deadlifting 200kg six months post-op:

(For comparison my best ever deadlift post-op was 245kg)

December 2025 (18 months post-surgery):

My best post-op lifts at this point:

- Deadlift 212kg x4

- Squat: 182.5kg x6, 190kg x4, 200kg x1

Though at a single rep stage these don't beat my bests, these squat numbers for 6 reps (not the max) are personal bests even considering my strength pre-training. 216kg x4 is the best I've ever done on deadlift pre-surgery, so I'm getting pretty close to that number too.

If you are curious to see how my training progressed to these numbers, here is a spreadsheet of my training progression over the last 18 months (June 2024 - December 2025). Note, I don't always record my accessory movements in this sheet but I am consistent with recording my top sets.

The Numbers You Actually Want (Without a Single Magic kg Limit)

I'm currently an off-season 78 kg, so bodyweight force ~ 78 x 9.81 ~ 765 N.

Note: The detailed kN anchors (stumble vs elite squatting) and the contact-pressure math live earlier in the article in Anchoring on Measured Hip Contact Forces (kN). I'm not repeating them here; this section is where I apply that intuition to the numbers people usually ask about.

Another question I wanted to estimate: Is 200-250 kg Fine? What About 300 kg?

Disclaimer (repeated because it matters): this section is not medical advice and is answering this for myself only from a materials + load-scale perspective (not "what surgeons usually advise"). Please don't use this as a personal clearance to lift.

200-250 kg deadlift:

- On strength-of-materials / peak-load grounds, it is hard to build a credible argument that this threatens the implant purely by compressing the liner or "punching through the cup", assuming centred contact.

- The OXINIUM head is absurdly strong relative to joint loads.

- The liner deforms rather than behaving like brittle ceramic-the contact patch grows under load.

- The realistic risk drivers are technique error -> twist/shock, and femoral-side fracture mechanics, not "the head snaps" or "the liner compresses into dust".

300 kg deadlift:

- Still unlikely to be "material failure territory" purely from peak force.

- But it pushes you further into the zone where small deviations matter more: hip impingement, slight rotation under load, loss of balance can create edge-loading / torsional spikes.

- Consequences scale nastily-you don't miss 300 kg gracefully.

- I'd call 300 kg materials-plausible, risk-gradient-steep: the plausible failure modes shift further toward biomechanical events (falls, torsion, periprosthetic fracture risk), not "the OXINIUM snaps".

Conclusion

My personal consideration of risk, reward, and resulting training approach

Getting back to powerlifting after a total hip replacement is a process that requires consideration of several factors, from the forces your implant can handle to the rate of osteointegration and the long-term impact on joint wear. Remember that while the calculations and estimations I've shared have helped guide my recovery, they're only part of the picture. These calculations are something I've done to help guide my own training safely, but it's crucial to listen to your surgeon's advice. They understand your specific situation and can provide tailored guidance that takes all these factors into account.

Regarding how these additional risks influence my training choices: I am 36, male, with no signs of osteoporosis, and my surgery was over four months ago (at the time of writing). I also believe my bones are likely stronger than average due to years of consistent powerlifting and maintaining a good diet (again, Wolff's Law). This further reduces my perceived risk. As a result, and reflecting on stories of other powerlifters returning to training after a hip replacement, I've decided that I'm prepared to take a measured risk and gradually return to lifting heavy weights in a controlled and cautious manner.

My goal moving forward isn't to determine what I can achieve for a one-rep max. Realistically, I don't plan on doing a one-rep max squat or deadlift again. The main reason is that I want to avoid putting my body under unnecessary stress and risking a technique failure, which could lead to a significant force multiple through the joint or, worse, torsion that could compromise the implant and lead to serious injury or dislocation.

In powerlifting, there's a concept called RPE (Rate of Perceived Exertion), which means lifting in a way that leaves some reps in reserve. For instance, an RPE 7 would leave three reps in the tank, while an RPE 8 would leave two. In practice, I don't intend to go beyond an RPE 8, and most of my training will likely remain around RPE 7. This approach allows me to progress with the weights, considering the guidance from the graphs, while avoiding lifting too heavily to the point where my form breaks down. It's a way to strike the right balance-progressing safely and getting enjoyment from lifting, without taking unnecessary risks.

For me, this feels like the right balance of risk, though I understand that the risk isn't zero. My surgeon advised that I could return to lifting, provided I avoid movements I cannot control well, and I plan to follow that advice. Ultimately, this is my personal judgment call and should not be taken as advice. As with the rest of this article, I simply want to share my thought process throughout this decision.

Always seek professional advice

UPDATE:

Using the kN anchor approach with measured hip contact forces (~12 kN at maximal effort), and keeping my built-in safety margins, the limiting factor is not material strength but osteointegration quality and avoiding bad loading conditions (edge loading, impingement). For me (78 kg off-season BW), the practical question isn't "what's my kg limit?" but rather "am I maintaining good hip mechanics and avoiding positions that risk edge loading or microseparation?"

Given these variables and uncertainties, the information I've shared should be taken with extreme caution! I'm not a trained medical professional, this is not medical advice, this article is not a peer-reviewed medical study, and there is a good chance I've made mistakes in my reasoning. Ultimately, the most important advice I can give is to work closely with your surgeon and physiotherapist, follow their recommendations, and take a gradual approach to increasing your load. The numbers might tell you what's theoretically possible, but your body-and your medical team-will tell you what's actually safe (I'm not a medical professional, and this is not medical advice! Please speak to a qualified medical professional to guide how you return to training post recovery).

Remember that many factors can influence the speed of recovery and the accuracy of the numbers I've calculated. Different implant materials, your age, strength, the presence of micro-movements in the joint in early recovery (which can impact effective osteointegration), or conditions like osteoporosis can all affect how well the bone integrates with the implant. Your diet, nutrition, sleep, and overall health will also play a role in the success of osteointegration.

If you've found this article interesting, you may also enjoy my hip replacement recovery diary and three-month post-op Q&A. Also please get in contact if you have any feedback or improvements about this article.

If you'd like to play with my numbers, you can download the Python script here that I created to calculate them and plot the graphs.

Key Takeaways (high-level, not medical advice):

- Early months are about bonding, not "metal strength": before osteointegration is mature, the key risk is micromotion/torsion compromising fixation - not the implant "snapping".

- There isn't one safe "kg limit": the relevant risks change over time (early fixation, mid-term femoral-side fracture risk, long-term liner wear). Treat any single number as misleadingly precise.

- Hip forces are often larger than people expect: published measurements/modeling put peak hip contact forces for events like stumbling and heavy squatting in the ~10-12 kN range. Barbell weight doesn't map 1:1 to joint force.

- Technique failures are the real danger multipliers: twisting, falls, uncontrolled reps, impingement, and edge loading can create "bad conditions" even when a controlled rep would be fine.

- Wear is mostly about cycles + contact conditions: long-term wear risk depends heavily on how often you load the joint and whether you avoid edge loading/microseparation - not just "one heavy rep".

- Use your medical team as the authority: this article is a personal reasoning exercise, not a rehab plan. Your surgeon/physio should guide your progression.

Appendix

Recommended Coaching

If you're after the same evidence-driven programming that helped me progress safely from the operating table back to 200 kg+ lifts, I can't recommend my coach, Luke Rogers, highly enough. Luke is a coach for the Great Britain junior powerlifting team, a former British Champion, and Head Coach at MSC Performance in Birmingham. His focus on technique, tempo, and load management has been crucial to my recovery. Whether you're coming back from surgery or simply want to push your strength further, I'd strongly suggest getting in touch. You can reach him on Instagram @luke_rogers_74, on Linkedin, or through the MSC Performance website.

For full disclosure, I don't receive any kickback from these recommendations. I'm recommending Luke simply because I've used his services for years and trust him. It's a personal recommendation, and I feel I owe him a thank you by mentioning him at the end of this article.